Eated: Is it ever correct?

A qualified yes, but mind your spelling

A weed-eater eating non-weeds.

It’s one of those blessed autumn days when the sun is out, the sky is blue in every direction, and the air is as crisp as a freshly cut apple. My wife and I are driving happily along the motorway towards Cambridge, a pretty, tree-lined town an hour from home, chatting away as people in a weather-induced state of bliss do. After a while our attention turns to our rural property. “Once we’ve weed-eated around the trees,” she says, “we can start mulching.”

That’s the thing about driving, which is her task today - it makes you forget how to speak proper English. The word she’s looking for is surely weed-eaten.

For my non-New Zealand readers, a weed-eater may also be called a line trimmer, string trimmer, whipper snipper, strimmer, weed wacker (or whacker), grass trimmer or any of a million other names I’ve probably yet to uncover. Weed-eating is what one does with a weed-eater. Followed, if one has any sense, by beer-drinking.

But that’s not the point. The point is my wife’s shocking grasp of English, which is clear on how verbs get treated as their tense changes. The present tense of to eat is eat, the simple past is ate, and the present perfect is eaten. You don’t need to know the names of the tenses to know how and when to use them - it got hardwired into your synapses soon after you started talking. And everyone knows when you’ve got it wrong.

Which my wife did, didn’t she? She was using the past perfect. So, surely, good English demands that she said “when we have weed-eaten.”

That was my initial thought. But initial thoughts be damned. On reflection, I think she chose the right word and that I can’t spell.

I think my wife was using the noun weed-eater as a verb. A noun as a verb? Sure. English allows you to verbify any noun you like, which is why you can google things on the internet while your partner texts a colleague asking them to action a request. If my wife was using weed-eater as a verb, she was well within her rights.

In that case, what she said was “when we have weed-eatered”. It’s every bit as unremarkable as if someone from another part of the world, where brand names are more cutesy, talked about having whipper-snippered the garden.

That’s unless she really did mean weed-eated. But even then, she may still have been within her rights.

That’s because, unlike the compound verb overeat, weed-eat doesn’t describe a kind of eating. In fact, it has nothing to do with eating in any real sense.

That means it doesn’t - and possibly even cannot - obey the same rules that a typical compound verb does.

Compound verbs like overeat normally modify the meaning of the “head” - the source verb that makes the longer verb possible. As the tense of the compound verb changes, it follows the same rules as the head does. Ate becomes overate and eaten becomes overeaten.

But weed-eat is, I think, a headless verb. Weed doesn’t modify eat, thus describing a kind of eating; the whole word names the act of whacking pesky plants with a nylon string, which has nothing to do with eating at all. So when you want to create the present perfect tense of weed-eat, you may well do what every child learned to do at an early age, and pop the letters -ed on it. Not weed-eaten, but weed-eated.

Steven Pinker covers this in his wonderful book The Language Instinct. It’s why multiple saber-tooth tigers are called saber-tooths and not saber-teeth and a collection of still life paintings are not still lives but still lifes.

One sabre-tooth tiger debating with another, before the publication of The Language Instinct, whether the plural is sabre-teeth or sabre-tooths.

This does raise another question, though. While I can hear whipper-snippered, whipper-snipped - the equivalent of weed-eated - does sound odd to my ear. I imagine Pinker would have something to say about this, and I must admit that at this point I can feel my toes only barely touching the bottom of the linguistic swimming pool. Maybe weed-eated is weird and not really English.

Which raises a further question: which word did my wife have in mind? You’ll be thrilled to know that I put that very question to her. Her reply: “I thought I said ‘weed-eaten’.”

If there’s a lesson anywhere here, and part of me hopes there really isn’t, it’s that any time you hear a fluent speaker someone say something that sounds a little dodgy, grammar wise, it’s wise to check that your hearing aid is on.

If it is, next ask whether your judgement may be off. Much of what sounds strange at first blush turns out, on closer inspection, to be not only sound, but appropriate in a way that your initial instinct can easily miss.

For example, the popular use of youse as the plural you may be non-standard English, but those who employ it are regifting English with a useful distinction it once had but then lost.

Likewise, when someone says of someone else’s misfortune, “I could care less”, they’re not being ignorant, they’re being sarcastic.

Native speakers rarely mangle their language for the same reason people don’t walk wrong. Language comes naturally to all of us and while some may use it in ways that are unique to them or their social group, they’re unlikely to be doing it “wrong”.

In fact, much of what people allegedly get wrong is simply a variation on what is considered the standard version of their language. Saying less for countable nouns, saying dived instead of dove, and saying drive safe instead of drive safely may break from what your style guide calls good writing, but not one of them disobeys any fundamental rule of English grammar.

So this story does have a moral after all, and it’s don’t get all moralistic about language. Far better to listen with a curious mind and see whether what appears at first sight to be a mistake may actually reveal some hidden facet of how the language really works.

Bits and specious

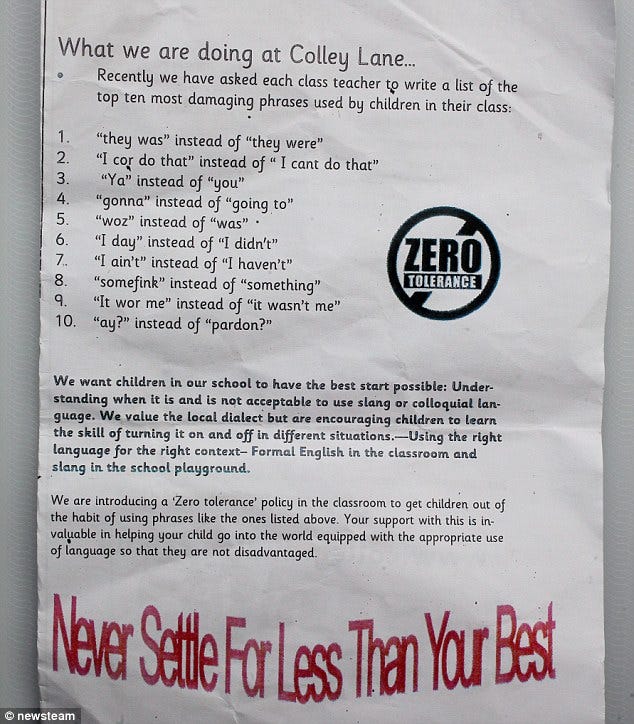

In an effort to give its children “the best start possible”, in 2014 Colley Lane Primary School in England’s West Midlands banned Black Country slang such as “it wor me” (“it wasn’t me”) and “I cor do that” (“I can’t do that”). The ban raised the ire of many locals, but the school reported an improvement in students’ performance. More here, including a quick guide on how to speak like a Yam Yam.

Never settle for less than your best, said Colley Lane Primary School. They weren’t codding, the blithyeds.

Earth is the only planet in the solar system not named after a Greek or Roman god. The reason? Our ancestors didn’t realise Earth was a planet. However, the word terra (as in terrestrial, terra firma, etc) does derive from Terra Mater, Roman goddess of the earth.

Some years ago, a famous English public school was forced to raise tuition fees. A letter was duly sent to parents conveying the unfortunate news that the increase would be £500 a year. Perhaps even more unfortunately, the typo per anum was overlooked. One parent wrote back, informing the school that “for my part I would prefer to continue paying through the nose, as usual”.

Quote of the week

If you are not killing plants, you are not really stretching yourself as a gardener.

JC Raulston

I think the operative rule here is: When a strong verb or noun is used in a foreign or figurative way, it becomes weak. Gray rodents are mice, but computer input devices are mouses. The wacker doesn't eat, it weedeats, which lost its connection with eating. So weedeated becomes a "foreign" or weak verb. But meat-eating is still strong, because it's just a compound on eat.

The/a prototypical example from the vocabulary of baseball is when a player hits a fly ball that's caught for an out. In other words, the player "flies out" and, in the past, he "flied out". Ain't no way that's ever going to be "flew out". ;)