Our vege garden. Father, my father, why have you forsaken me?

We’ve had a tough few weeks up here on the hill at Glen Murray. Lack of rain has seen our vegetable garden become dryer and dryer, and being on tank water means we can’t be turning on sprayers willy nilly. I’ve been watching tomatoes develop blossom end rot, perpetual spinach go all droopy, seedbeds refuse to germinate, and sheaths of sweetcorn peel back to reveal pathetic half-formed cobs you wouldn’t feed to your chooks.

Adding insult to injury is that to the east, in clear view from our eyrie, a steady procession of swollen rainclouds have been dispensing water upon the plains like a wayward priest at a baptism. Every so often, one will veer west, filling us with hope, before adopting the form of a raised finger and reassuming its eastward course.

For us, luckily, this is no tragedy; our garden is merely a hobby and we are no Tom Joads. When I was a youth it was not so. In the early 1970s a drought on the farm at Tomarata saw my father reduced at one point to tears - a sight so unthinkable that it rocked me to the core. In my childishly narrow view of life, though, my main thought was how delightful it was that the cows would stop producing early that season and I would not be required to help with milking during the coming autumn mornings and evenings.

Dry is a variation on the Middle English drie, which meant then what it means now. Drie came from Old English dryge, which came from Proto-Germanic.

Proto-Germanic, in case you’re wondering, lives in the same realm as Proto-Indo-European, or PIE for short. There is no direct evidence for either language - no written records that allow us to make definitive statements about them. But when linguists trace the history of changes in word sounds in known languages further and further back, it becomes obvious - if not inescapable - that some must share a common ancestor and that many features of that ancestral language can be confidently deduced.

Proto-Germanic emerged from PIE, probably around 500 BC. It shared consonants with its parent, with one notable omission being those formed at the back of the mouth and sounding - as far as I can gather - like the sound you make when you get a fish bone stuck in your throat.

In the absence of direct evidence for even its mere existence, you may think linguists are drawing a long bow to posit such specific theories on a language. But we do it - or at least experts do it - in many fields. When the planet Neptune was discovered in 1846, astronomers were already near certain of its presence based on irregularities in the orbit of Uranus. Through thought experiment alone, Einstein said in 1915 that gravity bends light - a claim that was proved right (to almost no scientist’s surprise) by observation of light passing near the sun during a solar eclipse in 1919. Likewise, 50 years passed before the effects of the Higgs boson - proposed by physicist Peter Higgs in 1964 - were actually observed in the Large Hadron Collider.

While theories about dead languages can’t be tested the same way as scientific theories, they are at least subject to scrutiny by hordes of linguists who, like scientists, are trained to sniff out a specious argument and are happy to pick it apart, publicly and mercilessly.

Before Proto-Germanic - and this tickles me more than it should really - came pre-Proto-Germanic. If I were being pedantic, I might also point out that proto generally means “first, source, parent, preceding, earliest form, original, basic”, which suggests an earlier form of a proto- anything should be more or less out of the question. But who knows what acrobatics get performed in the minds of linguists?

Proto-Germanic led to the Germanic languages, including German (of course), English, Swedish, Danish, Norwegian, Dutch, Afrikaans, Yiddish and Scots. According to SIL Global, a Christian organisation dedicated to the study of languages in order to promote literacy and the spread of the Bible, the world today speaks 48 Germanic languages.

But I digress. Drought, as you’d probably expect, is from the same source as dry. If you’re Scottish or from the north of England or of a poetic mind, you may prefer drouth. Drain, less expectedly, also comes from the same parent as dry - although when you think about what happens to something when you drain it, the link gets clear.

The first clothes dryer, a hand cranked device, was created in 1800 by a Monsieur Pochon from France. It took 137 more years before American Henry W Altorfer devised the electric clothes dryer and three years after that for his compatriot, Brooks Stevens, to design one with a glass window, which possibly says something about available entertainment choices at the time.

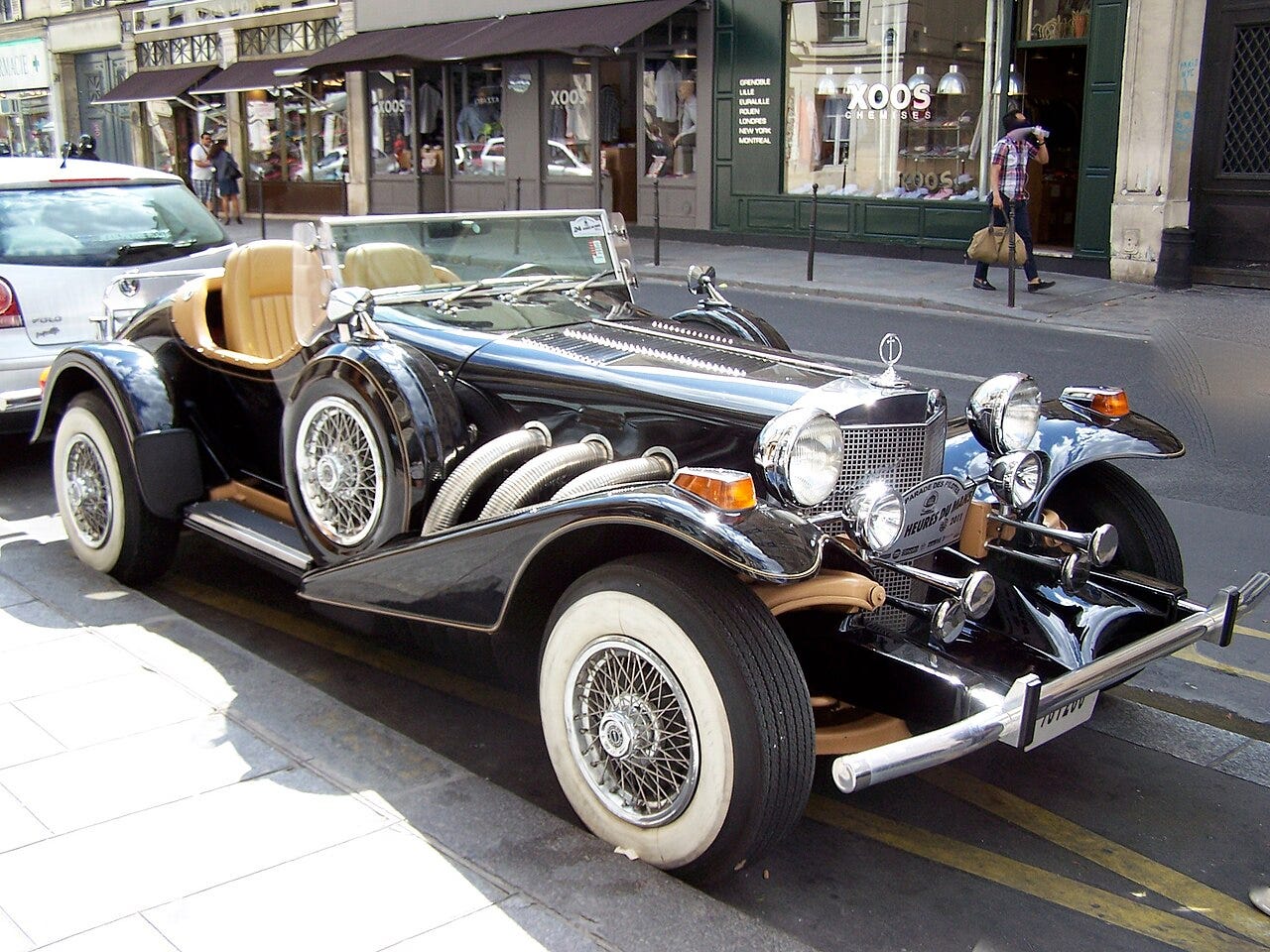

Stevens was no slug in the design department. He developed a host of home furnishings and appliances as well as cars, passenger railroad cars and motorbikes. He was also a noted graphic designer (he created the Miller Brewing logo) and stylist, who the New York Times dubbed “a major force in industrial design” in its 1995 obituary.

I want one.

Feast your eyes on this 1970s Stevens design, the Excalibur SS, and say The Times got it wrong.

As for our parched garden, about two hours after I began writing this keening post, a rain cloud - possibly confused about where it was - wandered over our way and dispensed a few welcome drops of water upon our thirsty crops. A mere one day later, as I wrap the post up, the entire sky is filled with grey clouds that look ready to do their thing in a big way.

Coincidence? Maybe, but I’m not taking any chances. Next week’s word: money.

Bits and specious

Along with its many well-deserved claims to fame, the Large Hadron Collider also holds one that its creators probably wishes it didn’t - one of the world’s most easily misspelled-with-funny-but-puerile-results names. Among the many who’ve fallen victim to this error is CERN itself, the organisation that funded and runs this magnificent machine.

A hadron, says Wikipedia, is a “composite subatomic particle made of two or more quarks held together by the strong interaction”. The word was coined in 1962 by Soviet physicist Lev Okun from the Greek hadros (“thick, bulky”) and the elementary particle suffix -on, also seen in baryon and meson. The hadrosaur, aka duck-billed dinosaur, got its name from the same Greek root.

Quote of the week

One way to help the weather make up its mind is to hang out the washing.

Marcelene Cox

'long time passing'...this 60s kid liked the song along with a fair shed-load of other more syncopated folky stuff. Can very recommend the Dylan flick.

SOrry to hear of the big dry your neck of the woods...certainly plays havoc with gardens when you can't fling a hose around with gay abandon. Keeping a garden alive is my main occupation right now but am in the Wigram burb so not a problem.

My 'come hither' to the sunshine is to leave the sunnies at home when venturing forth..never fails. Living on an old airfield means you can scan the skies (the subdivision is called 'Wigram Skies'), for rain & local forecasts are very reliable too.

With more Welsh programmes on the tv now I am reminded of my childish wonder at the new owners of the corner shop on Coro historically, with a Welsh lady who called people 'Bach' to my pre-teen ears, involving a back-of-the-throat sound like Dutch has. Gleaned that is was a term of endearment. Our German friends commonly scoff at things using throaty sounds.

Wish we still read about the LHC & all it's weird wonders for that was a time free of much the modern lunacy.

'the same Greek root' has to be handy...stealing it.