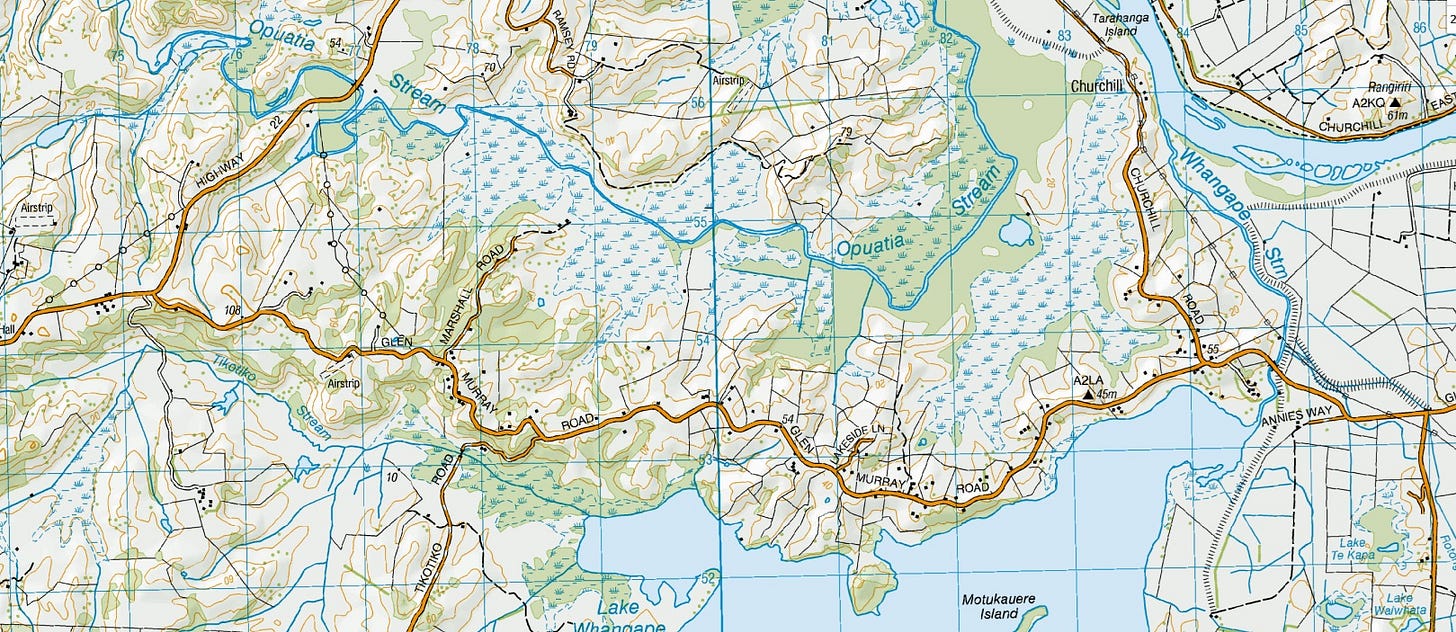

A map of the countryside near our home. Te Awa Waikato (Waikato River) curves through the top right corner, Lake Whangape is at bottom right. The speckled blue patches signify swamp. We’re not quite surrounded by water, but it’s close.

The morning after my wife and I moved to Glen Murray last summer, we woke to an impenetrable mist that had climbed its way overnight from the valley below. The view we’d been so looking forward to was blocked by a shimmering silver shroud that took most of that morning to lift.

We’d entered a realm dominated by New Zealand’s longest river, Waikato Te Awa. Ten kilometres east of us, it rolls its way towards Putataka (Port Waikato), its waters slowed to a sedate but implacable crawl by the surrounding plains that allow the river to spread itself out like a fat man loosening his belt after a massive binge.

Between us and the river lie three decent sized swamps, and to the south east is Lake Whangape - all products of the river’s faithless wanderings over the centuries; its refusal to be bound by the feeble demands of earthen banks. The result is a waterlogged landscape where relief is given only by whatever hills rise above the river’s reach as one proceeds west. It’s on the crest of one such hill that we live, overlooking - but not immune from - the damp world below.

For something so central to human existence, the word river is a surprisingly late addition to English. It entered the language in the early 13c., via the Anglo-French rivere and Old French riviere, which took it from the Vulgar Latin riparia, “riverbank, seashore, river”.

Before English had river, Old English had ea (pronounced ay-ah). While that word is lost to everyday use, you can still see it in place names like Eaton, which means “settlement by a river”, and Eamont, the name of a river in Cumbria, England. Ea is related to the Gothic ahwa, which springs (ha!) from the Latin aqua, a prefix we all know well, especially those of us with shares in bottled-water companies with grandiose names.

River’s meaning has barely changed over the years. All we’ve done since its arrival is introduce a figurative sense, as in anything that flows copiously (money from my bank account to my creditors’, blood from the paper cut I suffered the other day, etc), along with a few idioms like up the river (a place you don’t want to get sold). At one time in New Zealand, a child foolish enough to ask where their father was may have been told “he’s up the boohai shooting pukekos”, where boohai could be translated as river and pukekos were (and still are) a troublesome native bird. I say “could” be translated, because another explanation is that boohai is a mangling of Puhoi, a river north of Auckland that was considered remote before good roads were built. That saying has pretty much disappeared now, which is a good thing for those who think children deserve better (and that adults should do better), and a bad thing for those who like inventive and uniquely New Zealand sayings. I’m mildly ashamed to say I’m torn on the matter, but the better part of me says the idiom is now a little rustic for the urbane, single-source coffee sipping society we have become.

Somehow, things river related have been popping up a lot in my life lately. My fellow Substacker Emily Chenoweth recently posted about reading Norman Maclean’s great story A River Runs Through It. I’ve now begun reading it myself, having been deeply moved by the film in the early 1990s. (That no less a writer than Annie Proulx wrote an unabashed fangirl foreword to the book simply reinforces what a good decision I have made.)

I’ve also been travelling often between home and Auckland, a trip that requires crossing Te Awa Waikato in each direction. Every time I do, I’m struck by the imposing presence of the river, mindful too that by global standards it’s tiny (the Amazon River, for example, disgorges 209,000 cubic metres of water into the Atlantic every second; Waikato piddles a mere 340 cubic metres each second into the Tasman).

There’s something about the relentless, seaward flow of water that’s both awe inspiring and, for me, a little daunting. In my late teens, a frequently recurring dream involved trying to escape rising waters by seeking higher and higher ground - sometimes alone and sometimes as part of a group - and always being eventually, and inevitably, swallowed up. To this day, tidal swells unsettle me, which can be a challenge in an island country where causeways are common.

Not helping matters is that we’ve moved to a place not far from the infamous 1970 Crewe murders, which saw two young parents shot in their farm house and their bodies dumped in the Waikato. I was only 12 at the time and the case dominated national news for months (this was an era when murders were still rare.) A local man, Arthur Thomas, was convicted of killing them, but the case against him was weak and it was eventually discovered that police had planted crucial evidence against him. When he was pardoned nine years later, the case became officially unsolved once again. I can’t cross the bridge close to where Harvey Crewe’s body was found weeks after their disappearance without thinking of them.

On a lighter note, one of my happier childhood memories is of listening to the incomparable Stan Freberg, a comedic giant of the golden age of radio. My parents owned a double album called The Best of the Stan Freberg Shows, and it got a lot of play on the family’s radiogram.

One of Freberg and pals’ best skits, called Elderly Man River, parodied radio and tv censors’ urge to sanitise everything that fragile audiences might hear. Nearly 70 years on, it still holds its own, perhaps because we seem, once again, to live in an age that fears anything that might be even mildly discomfiting.

If you’re looking for more great river-related music, I recommend Take Me to the River - an Al Green song that sounds like the epitome of 1960s soul but was actually written in 1974 - and Find the River, which closes out REM’s masterful 1992 album Automatic for the People.

As I write, the river far below us is making its presence unfelt; the day is overcast and mist free. But what’s certain is that even with the warmth of summer just around the corner, we’ll have many more nights in the coming months where the cold mist rises slowly from the river, swamps and lake, sending its soggy tendrils slowly up the valley towards us. Come morning, we’ll wake, open the blinds, and mutter bad things about the bright wall pressing in against us.

And the elderly river, which was here long before us and will keep rolling along well after we’re gone, won’t give a good goddam - censors or no censors.

Bits and specious

In 2015, Storm Desmond caused massive flooding on River Eamont that led to the gorgeous 300-year-old Pooley Bridge, above, being washed away.

As radio audiences fell away in the late 1950s, Stan Freberg pivoted, as they say, and opened an advertising agency bearing his name. True to his subversive roots, its slogan was “More honesty than the client had in mind”. Despite this, he attracted General Motors and Mellon Bank to the agency’s roster and played a big role in the industry moving away from its previously stiff approach and adopting humour to win customers. The print ad above, which may not make it through the vetting process today, is a Freberg creation widely (and rightly) considered a classic.

When Talking Heads covered Take Me to the River on their second album, More Songs About Buildings and Food, theirs was just one of four versions in circulation at the time. Foghat (the group), Bryan Ferry and Levon Helm also covered it, prompting Talking Heads singer David Byrne to later write: “More money for Mr Green’s full gospel tabernacle church, I suppose. A song that combines teenage lust with baptism. Not equates, you understand, but throws them in the same stew, at least.”

Quote of the week

Never insult an alligator until after you have crossed the river.

Cordell Hull